Learning just the vocabulary of a language is not enough. We have to be able to put the words we learned together to form coherent sentences. Knowing the correct word order is an important milestone on a student’s way to language fluency. Indeed, it is one of the last pieces of the puzzle that, when fall into place, would illuminate every crook and cranny of an unfamiliar language. In this article, we will analyze the structure of a Chinese sentence, and from there create a foundation upon which we can build our language mastery.

Let’s start simple and pick an object for our example. The word for “house” in Mandarin is “fángzi ” (房子). The word for “one” is “yī” (一). To say “a house”, you would say “Yīgè fángzi” (一个房子).

This simple declaration of a thing has already taught us our first lesson, the use of classifiers, or measure words. Whenever you want to express the number of objects, you have to insert a measure word between the number and the noun. Furthermore, each type of object has its own measure word. One dog is “yī zhī gǒu” (一只狗); A piece of paper is “Yī zhāng zhǐ” (一张纸). The measure words act as an extra descriptive connector between the number and the noun. Papers are “zhāng” (“张”) , flat pieces, while books are “běn” (本), stacks of documents. There are some rough rules of when to use which measure word, but they are not definitive, you will just have to commit them to memory. Here is a small sample of some common measure words.

| Object type | Measure Word | Example |

| Packets or Parcels | bāo (包) | Yī bāo mǐfàn (a bag of rice) |

| Things bound together | běn (本) | Yī běn shū (a book) |

| Animals and parts of body | zhī (只) | Yī zhī gǒu (a dog) |

| Leaves or sheets of something | zhāng (张) | Yī zhāng zhǐ (a piece of paper) |

| Long, thin, or winding objects | zhī (枝) | Yī zhī bǐ (a pen) |

| Generic word, people and small objects | gè (个) | Yī gè rén (a person) |

A nice trick is to lump the classifier together as the first syllable of the word: “zhāng zhǐ,” (paper), “zhī gǒu ” (dog), “běn shū “(book). If someone mix up the measure word and say “zhī shū ” or “běn gǒu”, your brain should do a double take and cry out “that doesn’t sound right!”, because a dog is not a stack of documents bound together, nor is a book a long, thin, or winding object.

Let’s add a descriptive modifier to our object. “A yellow house” in Mandarin is ” Yī gè huángsè de fángzi” (一个黄色的房子). This step teaches us two more things. First, the adjective comes before the noun. The word for yellow is “huángsè”. And just like in English, you cannot say “house yellow” (“fángzi huángsè”), but you can say “That house is yellow” (“Nà ge fángzi shì huángsè de”).

Second, we introduced the usage of the word “de” (的). You will hear or see that word often in the Chinese language. The particle “de” has many usages. It can be used as a possessive modifier, i.e. ” Wǒ de fángzi” = “my house”; ” Nǐ de fángzi” = “your house”, “Mary de fángzi” = “Mary’s house”. It can also be used as a descriptive particle, linking an adjective to a noun: “Dà de fángzi ” = big house; “huángsè de fángzi ” = “yellow house”. And lastly, “de” can be tacked on to the end of a phrase to emphasize a declarative statement. “Wǒ huì zǒu de!” means “I will leave!”

Next, let’s form a complete sentence with what we’ve learned so far. We can say “Yǒu yī gè huángsè de fángzi” to state “There is a yellow house.” The word “yǒu” (有) means “to have”. To say “There is”, you really should say “Nàlǐ yǒu …”, where “Nàlǐ” (那里) means “there” in a physical sense. However, we can omit the “Nàlǐ” if we want to, it can be implied if we don’t care about the location. Saying “Nàlǐ yǒu yī gè fángzi” calls to the fact that a certain location has a house, whereas “Yǒu yī gè fángzi” merely states the existence of a house.

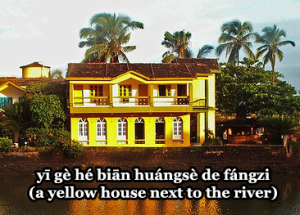

Let’s get more advanced and add another piece of information. To say: “There is a yellow house next to the river“, we would add “… zài hé biān” to the end of the sentence. “Hé” (河) means “river”, “pángbiān” (旁边) means “next to”, and “zài” is the linking preposition. “Zài” (在) is an extremely useful word, equivalent to the prepositions “at, on, in, under, to” in the English language. Also, notice the preposition “biān“ (next to) is tacked on to the right of the subject: “… zài hé biān,” and not before (e.g. you can’t say “… zài biān hé”). Our sentence now becomes “Zài hé biān yǒu yīgè huángsè de fángzi” (在河边有一个黄色的房子).

Lastly, let’s alter our sentence to express possessiveness of this wonderful house we’ve been describing. How would you say “The yellow house next to the river is ours”? From the lessons above, we’ve learned that we can add the word “de” after “Wǒmen” (we) to make it possessive: “Wǒmen de”. So let’s get rid of “yǒu …” (“There is …”) and replace it with “…wǒmen de” (“… is ours”) to the end of the sentence. This changes our sentence to “Zài hé biān huángsè de fángzi shì women de“.

There are a couple of subtle lessons shown in that last step. First, there is no word for “the” in the Chinese language. To say “The teacher”, you simply say “teacher” (“Lǎoshī”). To say “The Bell Tower,” you simply say “bell tower” (“Zhōnglóu”). This is why Chinese speakers have such a hard time learning this rule in the English language.

Second, we have to put all the modifying information of an object (“next to the river”, “yellow”) before the noun. “The yellow house” is “huángsè de fángzi”. The house next to the river” is “Hé biān de fángzi”. And because we have to keep “huángsè de” connected to “fángzi”, we have to move the piece of information regarding the relationship of the river to the front of the sentence (“Zài hé biān huángsè de fángzi”).

The Mandarin word “is/are/be” is “shì”. The information we add after “shì” is of course the main piece of information we are trying to convey. For example, we could say “Huángsè de fángzi shì zài hé biān” to express that the yellow house is next to the river (as oppose to next to a mountain or in the river). Or we could say “Zài hé biān de fángzi shì huángsè de” to express that the house next to the river is yellow (as oppose to white or red). In both cases, the piece of information after “shì” is the main point of the sentence. Hence, back to our original exercise, to say “The yellow house next to the river is ours”, we would say “Zài hé biān huángsè de fángzi shì wǒmen de” (在河旁边黄色的房子是我们的). Tada! All the words fall into place in their correct order to form a coherent sentence worthy of a fluent Chinese student.

Leave a Reply